I read the following at my mother’s funeral service.

I was in my early thirties with a new baby daughter, on a visit south to my mother’s winter abode in Florida, when—in our booth at Sam’s Delicatessen—my mom leaned across the table towards me conspiratorially, her eyes riveted on me as she seemed to be looking through me to her past. The urgency in her voice, a loud whisper, compelled me to listen rather than make a joke about her chest dangerously close to the yolks of her two poached eggs. She told me she wanted me to know how she had survived World War II and why she did not go crazy. Though she spoke as if revealing a long hidden secret, this would not be my first time hearing the story; growing up, I had heard it often.

“If my mother had not said what she said,” my mother continued, “I would not be here looking across the table at my grown daughter, now with a daughter of her own.”

There was something different in the telling and the listening that morning just months after my Naomi was born. I received the gift of my mother’s story as I never had before, knowing that when my infant daughter was old enough, I would share the story with her. My mother’s story is one of the most valuable gifts she has given me—in which she describes the most valuable gift her mother gave her, at a time when unfathomable despair—not invincible hope—might have been expected.

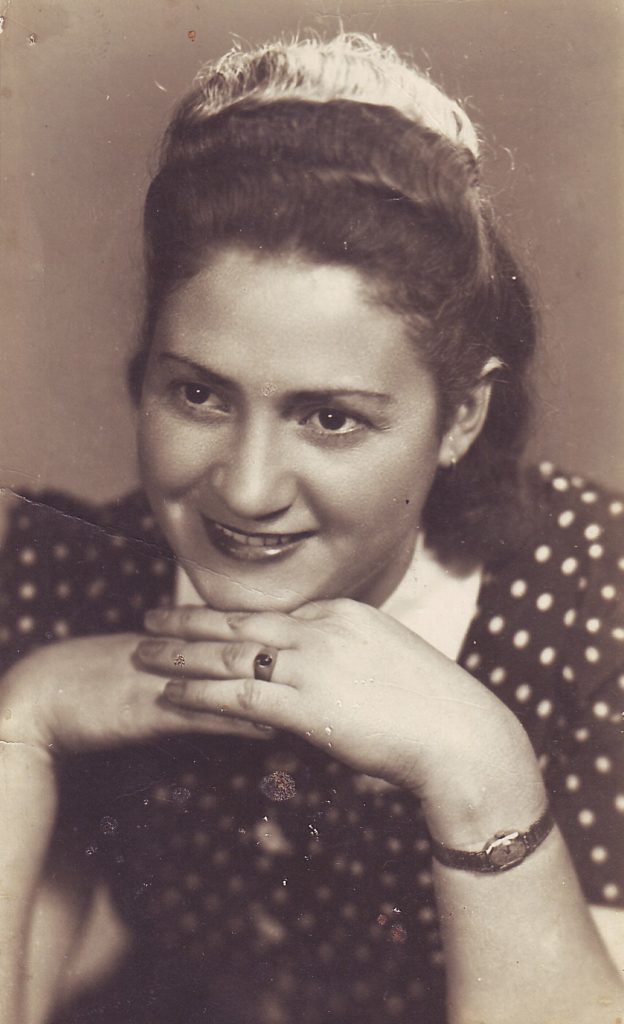

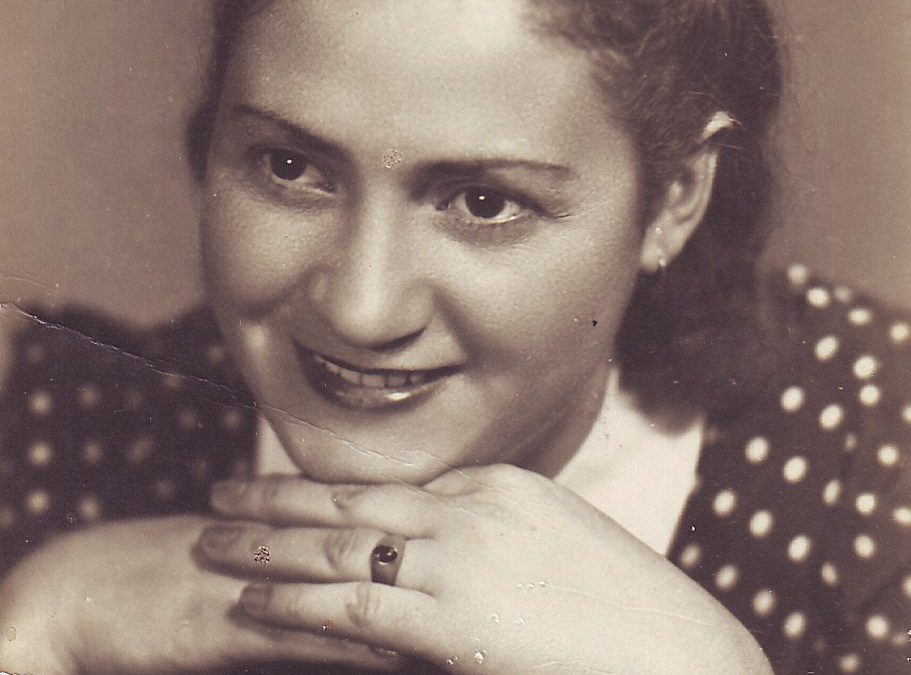

It was in the late 1930’s in the village of Kraznystav, that my grandmother, Channah, called my mother into the small room that had been their “general store,” a place for neighboring families to get flour, sugar, cloth— occasionally special items like the rare oranges brought by my grandfather from Lodz. My grandfather, Abish, was dead by then, their general store shut down by the Nazis. My grandmother closed the door behind her, asking my mother’s young brothers and sister not to enter.

My mother did not want to hear the words she had been fearing and hoping would never come. She braced herself even before her mother told her she was to leave Kraznystav, that she could save herself and must; the next time the Nazis came through the village, they would leave no Jews behind. My mother, fifteen, had red hair, spoke Polish fluently, could pass, her mother told her.

My mother did not want to hear the words she had been fearing and hoping would never come. She braced herself even before her mother told her she was to leave Kraznystav, that she could save herself and must; the next time the Nazis came through the village, they would leave no Jews behind. My mother, fifteen, had red hair, spoke Polish fluently, could pass, her mother told her.

There would be no arguing my mother knew, looking at her mother’s hands, trying to memorize the shape and length of the fingers, the texture of the skin. She watched one of the hands she would never see again reach slowly into an apron pocket and draw something out. Her mother motioned her closer and lifted something over her head. It was a thin chain—with a cross hanging from it.

Before my mother could utter her astonishment or question, she was silenced by her mother’s finger upon her lips. My grandmother proceeded then to teach my mother how to cross herself, to kneel, and to say the Lord’s Prayer in Polish, insisting she repeat it then— and from then on. She would not answer to Esther anymore; she would become Eva.

What happened next, my mother tells me, is what made it possible for her to survive the War; it gave her the will to live and the strength, again and again, to save herself when she wished instead to relinquish her life. Her mother pulled her closer and, whispering into my mother’s red hair, told her, “Remember, when God takes the father and God takes the mother, God becomes the father and God becomes the mother. Talk to God, my child. You will never be alone. Talk to your God.” These were the last words my mother heard from her mother’s lips before fleeing with the small brown valise her mother had already packed and pushed towards her, ordering her not to turn back.

My mother did talk to God those first nights after fleeing, huddled in the forest or crawling to drink water from troughs on peasant farms. She talked to God while she was a maid in a prominent Polish family in which the eldest son, who had been her brother’s friend and knew she was Jewish, hid her. She asked for God’s protection constantly, mostly without moving her lips. At night on a straw mat, she resisted sleep lest she call out to God in Yiddish and be overheard through the floor vents by the Nazis being entertained on the first floor. Later when she was moved to an abandoned barn and hidden beneath its floor boards, she continued to talk to God begging not only to be kept alive, but also that she be blessed with children one day.

My mother was blessed—with three children and nine grandchildren. What greater gift could a mother and grandmother pass on than the reminder to remember God’s love—to draw close always to the Source of all.

Now God has taken the mother and the grandmother. We can receive the gift of her words and faith, passed from her mother’s lips to hers to ours, a gift with the power to illumine the dark from the inside out. “When God takes the mother, God becomes the mother. Even when you think you are alone, you are not. Even when you think no one is listening, you are never alone. Talk to your God.“

God Bless You, Mom.

G'Mar Chatima Tova

I close with this customary greeting whose literal meaning is: "a good final sealing." I will add to that: May you know the love of which you are made. What better than to know this?

With gratitude,

Ani

Your comments make this blog a conversation!

I would love to hear from you.

To avoid spam all comments are moderated by Ani. So if you don’t see your comment show up, not to worry; your comment will be up within within 24-48 hours

Dear Ani

This is such a touching story about your Mother. She was so brave, as was your Grandmother.

Thank you so much for sharing this.

Love Karen

Thank you, Karen, for taking the time to read this and to comment. Yes, so brave. And because of that, here I am and my children and grandchildren. Thank God, for all of that…

Blessings on all the mothers and grandmothers who helped the Jewish children to survive the Nazis.

Blessings on all the mothers and grandmothers throughout history who helped all the children whose lives were in danger to survive.

My daughter is about to take her newly adopted daughter to the Mikveh to help her convert to Judaism. Given the current crisis of antisemitism, combined with the fact of my granddaughter being black, I see this as a great act of faith and courage.

Oh dear Judith! I love what feel like prayers of blessing… abundant blessings flowing to and through the mothers and grandmothers. Imagine if that kind of nurturing and fierce loving dominated our world rather than fear and all the rest…

How wonderful that your granddaughter is in a lineage of such love. Blessings on her head as well!

Keep me posted from time to time about her life’s journey. I sense it will be a powerful walk…

With love,

Ani

Oh Ani. That was beyond beautiful and so true. Thank you for your love and your amazing gifts to tell us such meaningful stories. Hope your Mother’s Day was exquisite.

Dear Cie, thank you so much for commenting here and for your kind words! What made my day more exquisite was, and is, feeling that what I offer from my heart (sometimes shyly) is received by other hearts. Thank you for that… 💜

Oh, Ani, I have no words. Only gratitude and tears.

Oh dear Caitlin, I SO know that place of no words. Only gratitude and tears. Thank you for sharing your heart with me in those moments.

Thanks so much dear for this post dear Ani.

A very fulfilling Mothers Day and everyday to you.

with love and blessings,

carol in Astoria

Carol, thank you for reading what I offered and for taking the time to leave a comment and to send me a loving wish and blessings–not only on Mother’s Day but EVERY DAY! Cannot ask for more!

Thank you for sharing…and happy mother’s day to you and Nomi..who I know are being held at all times by their mothers/grandmothers who continue to guide and inspire!

Amen, Sharyn.

It is true that I can feel my mother present with me and with my daughter Nomi and her children, who my mother never got to meet. There are tender moments with one or another of the tribe of grandchildren when I sense my mother’s delight, or moments of illness or threat when I feel her concern, even her protection. She had dementia for some years before she died and feels more present now than she did in those twilight years.

Thank you so much for your comment here that helped me to pause and reflect on your words about our mothers and grandmothers continuing to guide and inspire.

Brenda Shaughnessy, poet, wrote: The ones I loved

who died –why do I say I ‘loved’ why ‘died’

why not ‘The ones I love who die’

since that’s what I’m presenting here:

I love them, they still die. I am there.

Oh my Chris, these are powerful words: “The ones I love who die.” “I love them, they still die.”

They leave me silenced. Thank you for sharing them here.