Below is a piece I wrote (subsequently translated into Spanish) for “Memorias desde el Tugurio,” an important book about communities of “squatters,” shanty town dwellers, known in Colombia as ‘tugurianos,” and the rebel priest, Padre Vicente Mejia, who served them and transformed their lives, as they transformed his.

In a former life (in this incarnation), I was married to Orlando Isaza, a Colombian who introduced me to the tugurianos and to Padre Vicente. I hope that you will take the time to “meet” through my words these great teachers of love and be reminded of the love and dignity to be found where we might not think to look.

Teachers of Love: Los Tugurianas/os

Published (in Spanish) in Memorias desde el Tugurio by Eberhar Cano Narnajo

Compañeras. Compañeros.

Fueron Ustedes

que me dieron a entender

compañerismo.

You taught me something about love

I didn’t know until I met you.

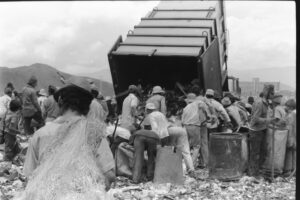

I was twenty. A gringa visiting from the US, being led to la basura, the city dump and to those that I had been told depended on garbage for their subsistence. I was being brought to witness.

Approaching, I smelled a stench so powerful, it felt like a wall pushing me back. I heard loud yelling, the sound of huge trucks. Cresting a small hill, I was stopped in my tracks at the edge of a scene that my eyes, mind and heart could barely take in.

Dozens and dozens of people, from elders to children, wielded homemade hoes, trying to keep their footing in mounds of ankle-deep garbage. They scavenged like their lives depended on it. And they did. A huge, loud garbage truck charged in, not slowing down, as if there were no people there at all. The people scattered only to regroup behind the truck when it stopped. Even before the driver released the back or lifted and began to dump his load, the people used their hoes to force open the back doors and pull at the contents as an avalanche of the city’s garbage it began to slide down towards them. More yelling as they backed away not to be buried by the mound, then lunged forward when the truck pulled forward.

Dozens and dozens of people, from elders to children, wielded homemade hoes, trying to keep their footing in mounds of ankle-deep garbage. They scavenged like their lives depended on it. And they did. A huge, loud garbage truck charged in, not slowing down, as if there were no people there at all. The people scattered only to regroup behind the truck when it stopped. Even before the driver released the back or lifted and began to dump his load, the people used their hoes to force open the back doors and pull at the contents as an avalanche of the city’s garbage it began to slide down towards them. More yelling as they backed away not to be buried by the mound, then lunged forward when the truck pulled forward.

I watched them work in the intense heat and stench, using hoes and hands in their avid, desperate searching, their findings tossed into sacks and cardboard barrels slung over their shoulders. Somehow, they made room enough for each to seek their subsistence. No one shoved another to compete for scraps nor inadvertently hit a nearby basuriego/a with a hoe. A bulldozer pushing through looked like it would plow the people in with the huge heaps it was forming. But nothing daunted the throng of souls in their quest, as if seeking treasure.

A small distance from the center of the action on smaller mounds of garbage, I saw a naked swollen-bellied child, maybe two years old, sucking on a rotten orange. Vultures circled over the child’s head.

That is when it all went black. I did not drop. (I think Orlando caught me before I did.)

I don’t know just how long that pitch black void was all there was, but when I emerged, I had no voice. I would not be able to speak for several more hours. I had been shocked into silence. I was stunned by the degree to which we humans can abandon others, can be indifferent to the needs, rights, and dignity of others in our human family. It felt unbearable.

I am no stranger to “man’s inhumanity to man.” I was raised in the shadow of the Nazi Holocaust of World War II, the daughter of Jewish Holocaust survivors, whose parents, sisters, and brothers were brutally and mercilessly killed in death marches, in trains filled with gas, and in concentration camps. My parents’ trauma and grief were as much a part of them as their skin. I had experienced my own direct trauma as well, shamed as a Jewish immigrant child in America, my hair searched daily on the school bus for my Jew-devil horns along with other abuses. But even with my knowledge and experience of the human capacity for cruelty, and maybe because of it, I was overcome at the edge of la basura by the extreme measure of inequity I was beholding. How could society dehumanize others to this degree? And remain indifferent?

What I did not know yet that first day on the edge of the city’s dump was that I would also come to witness and experience reflections of humanity that no measure of oppression and deprivation can take away. The tugurianas/os revealed the human capacity for kindness, integrity, and, above all, for love, despite circumstances that would seem to make such humanity impossible. But I am getting ahead of myself….

I recovered my voice later that night. Orlando and I returned the next morning. The last in a series of busses from Orlando’s mother’s home on the outskirts of the city deposited us at the top of a steep mud hill. It was at the bottom of this hill in a ravine adjacent to the city dump that the tugurianas/os lived. Much as I tried for it to be otherwise, I descended that hill on my bottom, the brown smears there greeted by shy laughter from the youngest of children shushed by their older brothers and sisters, until I joined in. Laughter quickly became our common language given my meagre (and laughable) Spanish.

It took only minutes for the entire “neighborhood” to be notified of our arrival. Children eagerly grasped our hands to lead us to their homes, the mud of the path covering their bare feet and our shoes. Their dwellings, many sheltering multigenerational families, were constructed from scraps of tin, wood, cardboard, newspaper, sheets of plastic, and rags. That these shanties, which had come to be called tugurios could remain standing in the rain and wind seemed impossible. But here they were.

We were invited into one shack after another by their residents with warm insistent bienvenidos and por favor called out to us. Often, we had to bend our heads to make our way in, our eyes adjusting to the dark as we were graciously invited to sit on the board where later family members would sleep head to toe to head. Sometimes the seat of honor was a crudely constructed stool or a three-legged chair, our hosts usually standing. In every one of the homes we visited, apologies were offered for not having any food or drink to offer, not even a tinto, a little black coffee. I assured my hosts that I was not hungry even when I was. The great hunger growing in me was the longing that they be fed and have clean, easily available water to quench their thirst.

Orlando translated as residents of the tugurios explained proudly that they had fought to keep these homes. I learned that their dwellings were deemed Illegal by the government. Peasants who had left the countryside to flee violence and seek better lives, they had come with hopes. But they were unwanted in Medellin. Squatters. In enthused voices, they explained how the government had attempted to raze their shelters with bulldozers but how members of the community had “sat in” in defiance with Padre Vicente, ready to die rather than lose their homes. And the bulldozers had retreated.

They prayed the bulldozers would not come back. But if they did, the people, with their cherished companion, the “rebel priest” Padre Vicente, at their side, would resist. Again.

When Orlando and I returned the next morning, several children were sitting at the top of the hill waiting for us. One of them held a cardboard box, gesturing that we take off our shoes. Orlando explained to me that they were insisting on protecting our shoes so they would not become covered in mud. They would watch over our shoes and my purse until our return to the bus. Two children drew close to support me as I removed my shoes. The same two then tried to keep me from going downhill on my butt. At the bottom of the hill, dozens of children, several women, and a handful of men were waiting, barefoot, in ill-fitting clothes, missing teeth that did not make their smiles one iota less radiant or heart-warming.

We came almost every day for the rest of our summer in Medellin. Orlando would meet with a group of women, helping them master reading and arithmetic. I was surrounded by the children, the small ones barely able to walk to those who were school-aged but could not go to school for lack of the required uniforms and shoes. Children joined us before and after their “work” in la basura or begging in the center of the city. Once in a while, one of the gamines, the begging children, reported scoring a handful of Lucky Strikes, “lookey streekeys,” peddling them one at a time.

The children taught me more than I could possibly teach them. Barely literate in Spanish, what could I offer? I watched and loved their exuberant faces. I held as many as I could on my lap and in my embrace. I Iaughed with them—often at me. (They never ceased finding listening to me speak English hysterical.) Only later would I more fully realize that reflecting their light back to these wonderful beings was a gift. I did not think of it that way at the time. It just came naturally. I would come to understand the power of being with another in the presence of love, an exchange that requires no words.

We would stay for hours, usually gathered in the small pavilion, too classy a name for the mud-bottomed makeshift shelter where we hung out. There, under a leaky roof bolstered by four poles, we held our “classes,” and there each Sunday, Padre Vicente offered Mass along with his profound respect for this community and his commitment to their human rights.

One morning, me sitting in the pavilion on a short stack of adobe bricks, an overripe browning banana was delivered into my hands. With it came the instruction that I not share; it was meant for me because I had no experience aguantando hambre, bearing hunger. Taken aback by this remarkable act of care, I also knew I would not, could not follow the instructions. There was no way I would eat in front of the throng of children, maybe forty of them, around me.

I peeled the banana slowly, careful not to let any of its soft body drop, doing my best to break it into the smallest pieces possible. I would stretch it as far as it could go. When I offered a first tiny bite to a gaunt boy near me, he shook his head. My eyes filled with tears, not prompted by pity but by deep feeling that is hard to name. I kept my hand outstretched, motioning that he take it. Very reluctantly, he finally did. I watched him pass it to his little sister who took it eagerly. I knelt then, giving the pieces to the smallest of children in front of me who, ravenous, were quite willing to receive the tiny bites. Even as I wished for a plethora of bananas, thinking of the loaves and fishes story, I knew that bunches of bananas this one morning would do little to assuage the constant hunger of these beloveds before me.

On one particularly sweltering day, a child was sent to the pavilion assigned the task of leading me with some urgency to one of the tugurios. Worried that someone was hurt, I hastened behind her. At the entrance of the shack to which I was led, a pregnant woman pulled me in, barring the way to the trail of children that always accompanied me. She insisted I sit, which I did, on the upside-down, lopsided barrel she indicated. Then, her eyes and smile flashing, she held out a crumbled, soiled napkin on which sat a small, dry roll. She had found and saved it for me from la basura that morning.

“Eat, Anita,” she urged, almost a command, “You have been here for over five hours. You must be hungry. You are not used to it like we are.” She walked a few steps back to a corner shelf, crossing the small room back to me with a paper cup in her hand, also crumpled, half-filled with some dark liquid. “Pepsi Cola,” she said. “You must be thirsty also.”

It felt like she was offering me her life in this act of incomparable hospitality. Again, my eyes and heart filled. I took a bite of the stale roll to receive her love offering and told her as best I could, more with gestures than words that I would share the roll and the Pepsi. She finally yielded and out I went into the dusk to pass out pieces, little more than crumbs, and tiny sips to the youngest of the children, the ones who would receive.

The tugurianas/os taught me unforgettable lessons about giving and about receiving. The following, perhaps the most challenging lesson in receiving.

At the end of our visits, Orlando and I had to climb the mud hill back to the bus stop (often risking missing the last bus, as we stayed longer and later.) Our ascents were filled with humor. And with surrender. A cadre of children would vie to be part of the chain to pull Anita up the hill, a task made more difficult by the daily heavy rains. We would laugh together as we had on my way down. When I made it up without soiling myself, the children would cheer.

One day, at the end of our first week of visits, the children evoked my tears not my laughter. A bucket of water hoisted up the hill by a ten-year-old girl was placed in front of me, behind me a small three-legged stool rescued from la basura. I was to sit and let one of the older children wash my mud-covered feet, then allow another to wipe my feet dry. A third who carried my shoes would help put them on my feet. All this, so I would get on the bus clean. I did not want to allow it. How could I let them wash my feet? I was no better than them. This was too much to accept.

Orlando urged me to not resist, to allow this expression of their love. This, he said, was something they could give us when they felt there was little else that they could offer. I knew how much of limitless value they gave me in each moment I shared with them. There was no way to possibly thank them enough. Orlando helped see that in receiving, I was also giving.

After leaving Medellin and returning to the US, we would find other ways to give, raising money: for shoes and uniforms so the children who wished to study could go to school; for walls, a roof, and floor to turn the open-aired pavilion into a place where medical students could visit and offer health care, where classes could continue, and Mass could happen in a more hospitable environment. But that would be later.

More than our dollars/pesos, although these were far from inconsequential, the residents of what became known as Barrio Fidel Castro, would tell us about the life-changing impact of having their inviolable dignity recognized and respected. They spoke of what it meant for them then to be seen and respected as equals.

The residents of the tugurios gifted us with their welcome. They came to trust that we genuinely saw the beauty of their souls—the radiant, untainted souls of children, women, and men whose outer circumstances had deprived them of so much, but could not take away their capacity to love. To love as generously as they did and do, some might call superhuman—and coming from people that have been deemed subhuman! The children, women and men who subsisted on the garbage of others offered us their riches.

Not only were Orlando and I blessed in all the ways described above when we were among them, we were also blessed by their prayers for us. Mi Dios le bendiga, may my God bless you, was a common refrain, a blessing that rained down on us as abundantly as the midday downpours creating mud gullies everywhere.

Not everyone had faith in a loving God, though by far the majority seemed to be sustained by their faith. Most seemed to hold (and hold onto) the belief that they were not alone. They continually gave thanks: Gracias a mi Dios, for this and Gracias a mi Dios for that. They exclaimed their gratitude to their Creator for shelter; for finding a big piece of tin in the dump to patch a leak; for the baby’s toes not lost to a nibbling rat in her sleep; for a few lookey streekeys to sell; for the cuadernos, the notebooks we brought to them and the pencils; for the pictures we took of them; for the glass or metal scraps harvested in the dump that could be sold for a few pesos to buy food that was not rotten, or plastic shoes, or a dress for a child’s communion. Each week, Padre Vicente reminded el pueblo, the people, that they are children of God, precious in His eyes, that their suffering is not ignored, that they are entitled to homes, to food. To dignity.

Most seemed sustained by their faith. But there were those who felt abandoned, who were angry at the inequities, at the government’s threats to bulldoze their homes, at the ways society marginalized their existence. Sometimes their anger spilled out towards their neighbors. Occasionally, I would hear about one stealing from another, or about jealousies. One sharp-tongued woman without a kind word for her neighbors, was called puta, whore, her nightly vocation known to all. She explained to me that her prostitution allowed her to put food into the bellies of her three children. So what if they called her puta, she said, punctuating her indifference with her own choice words.

I often wondered if her anger and the anger of others in the community fueled their drive to survive as my father’s anger at God had fueled his survival of the Holocaust. My mother, who survived the Nazis hidden under the floorboards of a barn, was also kept alive by her belief that God was with her, no matter how terrifying what was unfolding. My father, on the other hand, was furious at the God his people had worshipped so faithfully for abandoning them and allowing them to be led like sheep to slaughter. My father told me he knew he had to take things into his own hands; that would be the only way to survive. I witnessed the tugurianas/os—faith or no faith—take things into their hands to survive and to keep their children alive.

It was amazing grace that I had the opportunity for a period of my life to meet such great teachers of love, to encounter their integrity, resilience, and above all their love.

My time with the tugurianas/os showed me the worst about humanity: how we can be indifferent to the needs of in our human family and contribute to their suffering by our indifference to devastating inequities. But my time in the tugurios also showed me the best about what makes us human: our capacity to sustain love in the worst of conditions.

Before closing, I want to share the following, excerpted from a poem I wrote and shared upon returning from Colombia to the United States:

Doña Marina, wearing a burlap sack—

holes cut for your arms, bare feet in the mud,

one eye glazed like an opaque marble,

the other focused on me—

you said, Tell them.

Tell them I am a mother, too.

I love my children no less.

I have buried three. Two no longer

can stand on their legs, their hair whitens.

Tell them.

Tell them I am a mother, too.

I will always remember these brave, tenacious souls radiating dignity despite the extreme, inhumane circumstances of their lives. They were and are my teachers of love.

Nunca olvidere lo que me han enseñado, mi estimados compañeras y compañeros. Dios les bendiga y les libere.

G'Mar Chatima Tova

I close with this customary greeting whose literal meaning is: "a good final sealing." I will add to that: May you know the love of which you are made. What better than to know this?

With gratitude,

Ani

Your comments make this blog a conversation!

I would love to hear from you.

To avoid spam all comments are moderated by Ani. So if you don’t see your comment show up, not to worry; your comment will be up within within 24-48 hours

Dear Ani

Again, you write your astonishing words and tell the teaching stories of your life and again, I cry. I cry for all of us who live less than any human should have to live.

I cry for the incredible love and giving that shines through none the less.

I cry for your precious heart and all the children who were gifted by your love

and I cry for all of us who become more compassionate, open hearted and caring because of the gifts you share with your words.

I send blessings of thanksgiving to you and your enormous loving presence on our earth.

Namaste

Oh my, Elaine. How powerful and filled with feeling is all that you have shared. A long time ago, my/our meditation teacher spoke of tears of love and longing as bathing the heart. That’s how I feel reading what you’ve written. There are tears and there are tears. The tears you describe are saturated by love and longing that strengthen. I send to you also, gratitude for your loving presence in our world. Namaste, dear one.

Ani, your beautiful soul that comes out in everything you write is overflowing with love. I am touched and drawn to your memories and creations on these pages. Thank you for giving me anguish, love and hope through your blessed eyes, mind, soul and eventually words. My love to you my friend, now and forever.

Dear Linda, I am so moved by your words. What a gift it is when the love that one wants to offer is so fully received. Thank you for THAT. 🙏🏽💜

Dearest Ani,

This piece needs to be as widely known as your “Angels on the Clothesline.”

Another example of “Man’s inhumanity to man.”

Bless you.

Janet

Dear Janet,

Yes, yes, another example of “man’s inhumanity to man.” And also, thankfully, an example of the indomitable love of which we humans are capable—the best of our humanity. How much I/we hope that Love will prevail. 💜

Ani, I am just blown away and devastated in ways by this piece, finding it hard to imagine what’s next? Do I get up now and walk the beach, enjoying the beauty and sounds and warmth of the sun the sand and breaking waves at my side? It seems so self indulgent, considering what I’ve just read.

We’re hosting friends for breakfast this a.m. I’ve been “stressed” with considering what to choose to put on the table, not to overwhelm ourselves and our 48” table with too much food for the four of us to undoubtedly over eat.

What do I do, as I sit surrounded by the beauty of our home’s luxury, as I think of the “homes” the plight, the challenge of hunger of so many on this very challenged planet. The ubiquitous question that I’ve asked in every decade of my life.

Thank you for this incredibly powerful piece that you shared with me with such passion 5 decades ago, and it continues to stop me in my tracks to contemplate, very simply:

How do I remain grateful for the incredibly blessings we have been given.

How do I remain conscious of the unbelievable suffering of so many on this planet?

How do I always remain aware and sensitive to the challenge of so many and give from the much I have in tangible gift and love and kindness and political action?

Thank you for this piece today.

Dear Marty, You ask such deep questions. I feel that embedded in your comments are responses to those questions. You are remembering, remaining conscious, grateful, and aware. And as we know, it is not our guilt that will change the world, but our loving commitment to true justice for all. May we keep remembering and feeding our passion for justice and equality. 🙏🏽💜

Ah Ani, thank you for sharing another part of the remarkable life you’ve led and yet more aspects of love and the compassion with which you assist people. May Love multiply in your life.

Thank you, dear Cie, for taking the time to read this and to comment here.

Loving compassion is the key, I believe, to open the way to a better works for all of us.

“May love multiply” in my life is a wondrous blessing to give me.

Thank you, again.